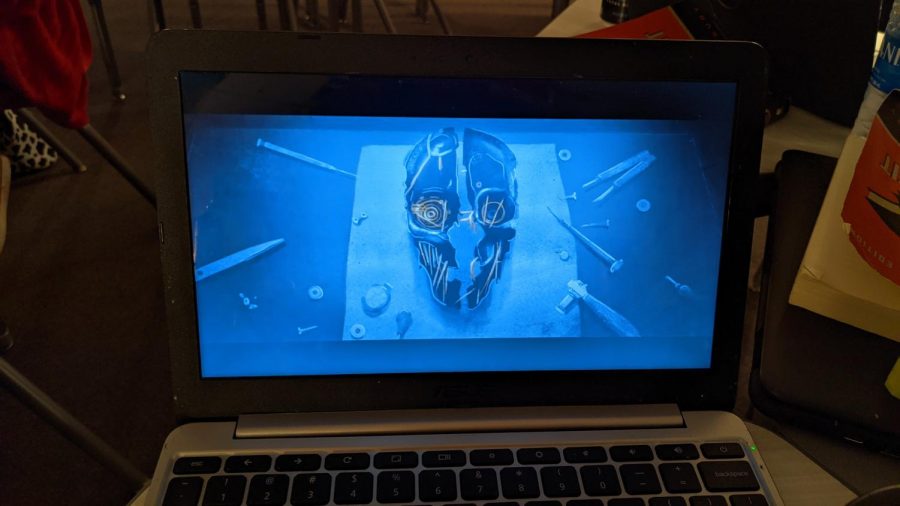

How Does ‘Dishonored’ Use Player Choice?

In Dishonored, revenge is a dish best served cold or however else a player chooses to serve it.

August 23, 2021

Violence in media has, for the longest time, been a controversial topic, especially in video games. The history of violence in games is long to say the least, and the debate over whether or not there is a correlation between violent behavior and violent games continues.

Violent games seem to flood the industry. They have become the norm, rather than the exception, and many people worry about the desensitization caused from such games.

However, there has been an interesting shift in focus towards violence in gaming, and that is the question of “How does it affect the story?”

The choices of a character, whether they are good or bad, can have very decisive narrative repercussions that could ripple throughout that world and affect people both in the story, and in the real world. It shows that one’s actions DO have consequences.

Enter 2012’s “Dishonored.” At face value, the immersive simulator seems fixated on providing players with a revenge-filled fantasy, but under this steam-powered veneer, there lies a game that provides a clever commentary on how violence can truly affect your world.

In the fictional, plague-ridden streets of Dunwall, you play as Corvo Attano, a bodyguard to the royal family who is framed for the murder of the city’s Empress. Forced to become an assassin, you carve away a path of retribution and violence as you slowly unravel the conspiracy that has taken root in the city.

Dishonored’s presentation is offered up in a very unique way. Stylishy cell-shaded and dripping with atmosphere, the streets of Dunwall feel lived-in and eerie. This dismal mood is only further enhanced by Daniel Licht’s provocative score.

The world-building is rich and interesting. The developers took a lot of time to flush out the political structure, beliefs and mythology of Dunwall, making it feel like a unique and tangible place.

However, the gameplay feels especially well-crafted. Corvo’s movements as you leap and jump across the rooftops of Dunwall feel agile, effortless, and almost cat-like. The combat feels equally fun and crafty, with take-downs and kills being brutal and visceral.

The developers took great care to create a game that allows one to approach it any way they see fit and still have that path be the correct path. This creates a sense of individuality for the player.

This is where Chaos comes into play.

In game, Chaos is a mechanic that is used to measure the morality of the player. Not only are the combat encounters affected directly by the player’s violence, but so is the game’s narrative. Measured in severity of high, medium, or low, the deadlier the player is, the darker Dunwall becomes.

Beginning in a state of low chaos, the player automatically starts with an advantage. Fewer enemies, rats, and guards spawn around you, and missions will have less harrowing narrative results.

However, by killing guards or civilians, getting spotted, or setting off alarms, a player’s chaos level is raised. This forces a player to act with more intentionality.

Being forced to decide on whether or not to act violently can cause some players to be more calculating with their approach.

They may have to engage more sparingly, avoiding certain paths and obstacles. And when they do encounter enemies, non-lethal takedowns are employed instead of killing, such as luring away guards or choking out a target.

Because of this, the story’s plot is directly affected by the player. Dunwall seems less dreary. You’ll receive less criticism from allies. People’s lives can be saved, and even the ending of the game can be more hopeful.

In a stark contrast to this, a high chaos player has an overall tougher game to fight through. Due to all the killing, the city watch goes on high-alert. This automatically inverts the difficulty curve for the player.

Combat becomes more messy and more chaotic. The bodies began to stack higher and higher, only resulting in more swarms of enemies to swim through.

Dunwall, in turn, becomes a mirror image of the player, a reflection of their actions. The higher the body count, the worse things become narratively.

You will be chastised by friends and allies, who have become disgusted by your remorseless killing. Enemies will be more afraid of you, and people who you have come to trust will begin to plot against you.

Even the ending is affected cosmetically, with a roaring thunderstorm looming over the location of Kingsparrow Island, making terrain harder to traverse.

These choices shape how the player comes to define Corvo as a character. Is he a violent, merciless assassin overtaken by hatred and anger, or is he a quiet, thoughtful and calculating rebel fighting against his circumstances?

Overall, this offers up a surprisingly poignant commentary on real-world violence. In the heat of the moment, violent behavior might seem easy, and it might even seem good for a season. But, long term, it will only birth more suffering and loss.

“Dishonored” commits to this idea. It reacts to the player’s choices precisely and thoughtfully, encouraging engagement with its narrative from the player. It wants to make you think about what sort of consequences your choices will create.

In the end, revenge doesn’t solve everything. It only complicates things. Violence only begets more violence. We all make decisions, but in the end, our decisions end up making us.